About Henry Johnson

In presenting the Medal of Honor posthumously to Henry Johnson and William Shemin on June 2, 2015, President Barack Obama told the story of Henry Johnson this way:

As a young man, Henry Johnson joined millions of other African-Americans on the Great Migration from the rural South to the industrial North -- a people in search of a better life. He landed in Albany, where he mixed sodas at a pharmacy, worked in a coal yard and as a porter at a train station. And when the United States entered World War I, Henry enlisted. He joined one of only a few units that he could: the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment. The Harlem Hellfighters. And soon, he was headed overseas.

At the time, our military was segregated. Most Black soldiers served in labor battalions, not combat units. But General Pershing sent the 369th to fight with the French Army, which accepted them as their own. Quickly, the Hellfighters lived up to their name. And in the early hours of May 15, 1918, Henry Johnson became a legend.

His battalion was in Northern France, tucked into a trench. Some slept -- but he couldn’t. Henry and another soldier, Needham Roberts, stood sentry along No Man’s Land. In the pre-dawn, it was pitch black, and silent. And then -- a click -- the sound of wire cutters.

A German raiding party -- at least a dozen soldiers, maybe more -- fired a hail of bullets. Henry fired back until his rifle was empty. Then he and Needham threw grenades. Both of them were hit. Needham lost consciousness. Two enemy soldiers began to carry him away while another provided cover, firing at Henry. But Henry refused to let them take his brother in arms. He shoved another magazine into his rifle. It jammed. He turned the gun around and swung it at one of the enemy, knocking him down. Then he grabbed the only weapon he had left -- his Bolo knife -- and went to rescue Needham. Henry took down one enemy soldier, then the other. The soldier he’d knocked down with his rifle recovered, and Henry was wounded again. But armed with just his knife, Henry took him down, too.

And finally, reinforcements arrived and the last enemy soldier fled. As the sun rose, the scale of what happened became clear. In just a few minutes of fighting, two Americans had defeated an entire raiding party. And Henry Johnson saved his fellow soldier from being taken prisoner.

Henry became one of our most famous soldiers of the war. His picture was printed on recruitment posters and ads for Victory War Stamps. Former President Teddy Roosevelt wrote that he was one of the bravest men in the war. In 1919, Henry rode triumphantly in a victory parade. Crowds lined Fifth Avenue for miles, cheering this American soldier.

Henry was one of the first Americans to receive France’s highest award for valor. But his own nation didn’t award him anything –- not even the Purple Heart, though he had been wounded 21 times. Nothing for his bravery, though he had saved a fellow solder at great risk to himself. His injuries left him crippled. He couldn’t find work. His marriage fell apart. And in his early 30s, he passed away.

Now, America can’t change what happened to Henry Johnson. We can’t change what happened to too many soldiers like him, who went uncelebrated because our nation judged them by the color of their skin and not the content of their character. But we can do our best to make it right. In 1996, President Clinton awarded Henry Johnson a Purple Heart. And today, 97 years after his extraordinary acts of courage and selflessness, I’m proud to award him the Medal of Honor.

We are honored to be joined today by some very special guests –- veterans of Henry’s regiment, the 369th. Thank you, to each of you, for your service. And I would ask Command Sergeant Major Louis Wilson of the New York National Guard to come forward and accept this medal on Private Johnson’s behalf.

MILITARY AIDE: The President of the United States of America authorized buy Act of Congress, March 3, 1863, has awarded in the name of Congress the Medal of Honor to Private Henry Johnson, United States Army. Private Henry Johnson distinguished himself by extraordinary acts of heroism at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a member of Company C, 369th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Infantry Division, American Expeditionary Forces, on May 15, 1918, during combat operations against the enemy on the front lines of the Western Front in France.

In the early morning hours, Private Johnson and another soldier were on sentry duty at a forward outpost when they received a surprise attack from the German raiding party consisting of at least 12 soldiers. While under intense enemy fire and despite receiving significant wounds, Private Johnson mounted a brave retaliation, resulting in several enemy casualties. When his fellow soldier was badly wounded and being carried away by the enemy, Private Johnson exposed himself to great danger by advancing from his position to engage the two enemy captors in hand-to-hand combat. Wielding only a knife and gravely wounded himself, Private Johnson continued fighting, defeating the two captors and rescuing the wounded soldier. Displaying great courage, he continued to hold back the larger enemy force until the defeated enemy retreated, leaving behind a large cache of weapons and equipment and providing valuable intelligence.

Without Private Johnson’s quick actions and continued fighting, even in the face of almost certain death, the enemy might have succeeded in capturing prisoners in the outpost and abandoning valuable intelligence. Private Johnson’s extraordinary heroism and selflessness above and beyond the call of duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, Company C, 369th Infantry Regiment, 93rd Infantry Division, and the United States Army.

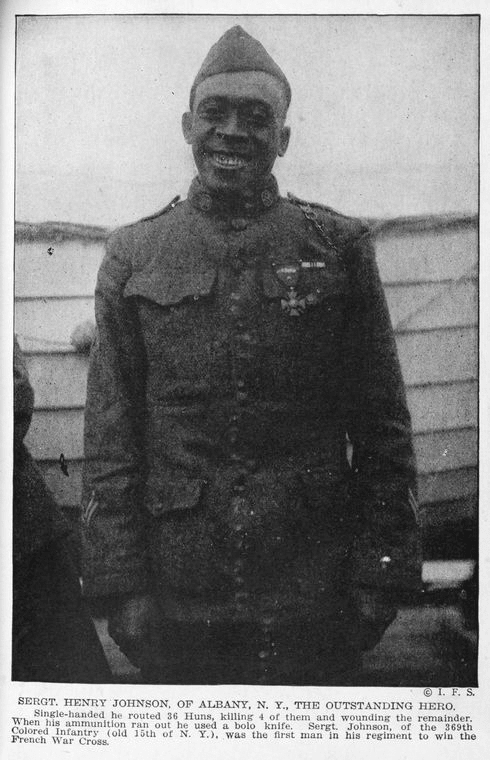

Johnson in 1919.

The Plaque at the Baron Hirsch Cemetery featuring Sgt. William Shemin and Sgt. Henry Johnson’s names.